Miywasin Moment: Brides in braids: Indigenous wedding traditions, Part 2

By JoLynn Parenteau on June 15, 2022.

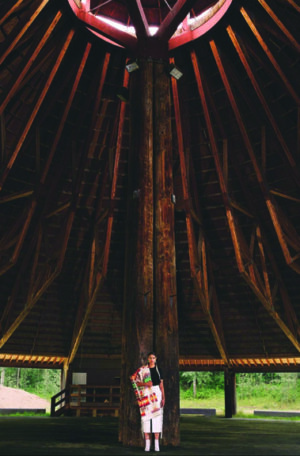

First Nations weddings were traditionally performed at natural sacred sites, in spiritual lodges, or wooden shelters called arbors. Modern Cree bride Ashley Callingbull is shown standing in Enoch Cree Nation's arbor.--PHOTO FROM INSTAGRAM @ASHLEYCALLINGBULL

This week’s Miywasin Moment concludes a series exploring traditional Indigenous wedding elements from across Turtle Island (Native North America).

Native American wedding attire

A Pueblo bride’s dress was a cotton garment tied above the right shoulder, belted at the waist.

A Navajo bride’s dress was woven with symbolic colours: white for the east, blue for the south, yellow or orange for the west; and black for the north. Silver and turquoise jewelry were worn by both men and women in attendance as a shield against evils including bad luck, hunger and poverty.

A bride from the Delaware tribe would wear a knee-length deerskin skirt and a beaded wampum band around her forehead. Winter brides would wear deerskin leggings, moccasins, a turkey feather robe and her face would be painted with red, white and yellow clay.

A Hopi bride’s wedding garment was woven by the groom and men from the village, and included a red-striped white robe, a wide belt and string to tie her hair, white buckskin leggings and moccasins.

Wedding gifts

The exchange of gifts between the couple and their families was common as part of the counting period and the marriage ceremony.

A Hopi young woman who had decided on a future mate would present him with a loaf of qomi bread made of a sweet cornmeal. This was an invitation to be engaged, so young men only accepted if they were ready to agree to be married. A male Hopi suitor would propose by leaving the bundle of fine wedding clothes on a maiden’s doorstep. Accepting the gifts secured the engagement.

A Delaware Native American couple’s joining was marked with an offering of blankets, jewelry, or a belt of wampum beads to the bride’s parents. If the parents accepted the gifts, the union was approved.

The Cherokee exchanged food with their vows. Grooms gifted their brides with venison to symbolize their ability to be good providers; the bride gifted corn or fry bread to indicate she would be a good homemaker.

A Pueblo groom’s parents would gift the bride with a sacred wedding vase with two spouts and a handle between, representing the bridge between both their lives. On their wedding day, holy water filled the vase and the bride and groom each drank from their own spout, symbolizing both individuality and unity, similar in significance to the exchanging of rings.

The future Algonquin bride and groom made or bought hundreds of gifts to give to their guests at the celebration.

Celebrations

Marriages were celebrated with feasts and dancing. Native American love songs were played by men on flutes.

A Navajo wedding included white corn meal to represent the man, and yellow for the woman. The corn meals were blended and stored in a basket. The wife and husband were considered equal partners, and the newlyweds shared the maize pudding during the ceremony to symbolize the union. The bride’s family provided a feast the next day, with any leftovers given to the groom’s family, completing the ceremony. First Nations feasts featured traditional dietary staples: beans, corn, fry bread, potato soup, venison, squash and fresh berries. The meal was served on a blanket and blessed.

Legend of the Ghost of the White Deer

A brave warrior, Blue Jay of the Chickasaw Nation, fell in love with the chief’s daughter Bright Moon. The young man was not well liked by the tribe leader, who demanded the hide of a white deer as the princess’ bride price, sure that Blue Jay could not capture the rare and elusive albino deer. White animals are sacred, and a white deerskin was favoured for a wedding dress.

Weeks passed and the young warrior grew weary in his hunt. On the night of the full moon, Blue Jay came upon a white deer. His best arrow pierced the deer’s heart. In a rage, the deer ran down Blue Jay with its sharp antlers.

Time passed and the tribe agreed that the princess’ betrothed would never return. But Bright Moon never wed another, for she held a secret in her heart. When the moon shone as brightly as her name, she often saw the white deer in the smoke of the campfire, running, with an arrow in its heart. She dreamed of the day the deer would finally fall, and Blue Jay would return to her.

To this day the white deer is sacred to the Chickasaw People, and for many generations the white deerskin remained favoured for a wedding dress.

JoLynn Parenteau is a newlywed Métis writer out of Miywasin Friendship Centre. Column feedback can be sent to

jolynn.parenteau@gmail.com

23

-22

First Nations weddings were traditionally performed at natural sacred sites, in spiritual lodges, or wooden shelters called arbors. Modern Cree bride Ashley Callingbull is shown standing in Enoch Cree Nation's arbor.--PHOTO FROM INSTAGRAM @ASHLEYCALLINGBULL

First Nations weddings were traditionally performed at natural sacred sites, in spiritual lodges, or wooden shelters called arbors. Modern Cree bride Ashley Callingbull is shown standing in Enoch Cree Nation's arbor.--PHOTO FROM INSTAGRAM @ASHLEYCALLINGBULL