Smoke, spies and open range brought blasts to SE Alta.

By Special to the News Stephen Murray on July 17, 2024.

The headline on the

Medicine Hat News read “Blast will dwarf 1961 detonation” on May 26, 1964, a reference to the upcoming Operation SNOWBALL at the Defence Research Station in Suffield.

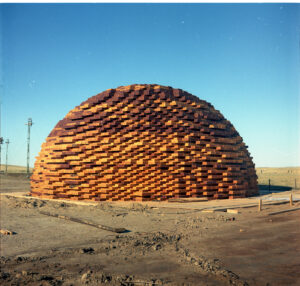

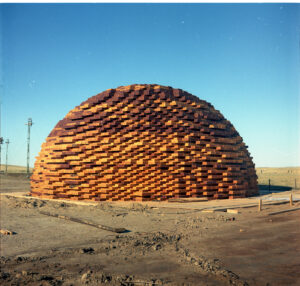

It involved the detonation of 500 tons of TNT, meticulously stacked in a dome shape, at 10:58 a.m. on July 17, 1964 – the largest non-nuclear surface detonation ever conducted at the time.

It followed a 100-ton detonation, simply known as Field Experiment 538, in 1961, and would lead to two more large blasts over six year in a tripartite tests by Canada, the United Kingdom and United States.

They came together in Southern Alberta a decade after spy scandals severed their partnership, after local scientists developed critical measurement processes and could offer a large 2,700-square-kilometre test range away from population centres. Suffield Experimental Station was given the task for a combination of practical and political reasons after spy scandals in the American and British nuclear programs.

Klaus Fuchs, a German-born British scientist, helped develop the atomic bomb, though at some point began passing top secret information about British progress to Soviet agents.

In late 1943, Fuchs was among a small group of British scientists brought to work on the American’s Manhattan Project. Fuchs continued his clandestine dealings with Soviet agents, and returned to Great Britain after the war to continue work on Britain’s atomic bomb project.

However, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation decoded Soviet messages that implicated Fuchs as a spy, and he was arrested by Scotland Yard in early 1950. He eventually admitted his role and served nine years in prison, setting off a chain of arrests.

Harry Gold, the middleman between Fuchs and the Soviets, informed on David Greenglass, a machinist at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project. Greenglass implicated his sister and brother-in-law, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. They were arrested in New York in July 1950, found guilty, and executed at Sing Sing Prison in June 1953.

As result, all nuclear cooperation between the U.S. and U.K. ceased. The British began their own independent nuclear testing program in 1947. The first British nuclear test, code-named Hurricane, took place in the Monte Bello Islands in Western Australia on Oct. 3, 1952. Eleven more would follow over five years, while over that time the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was analyzing its own nuclear tests using high-speed photography of shock waves against a background of white smoke trails.

The British wanted to do the same, and looked to Canada. Suffield was Canada’s principal research centre for biological and chemical warfare, including work to study smoke screens. In need of a measurement technique using smoke, the task was assigned to Suffield, with Ross Harvey as the team leader.

Cooperating with the AEC and the U.S. Naval Ordnance Laboratory, local researchers eventually secured smoke rockets from the U.S. Navy. Suffield scientists took up the question in 1955 and 1956, eventually developing a suitable smoke pattern on the low horizon that, against which, the speed of shockwaves could be measured by cameras capturing 100 images per second.

The equipment was shipped for use in Australia, where a small team of Canadians observed under a veil of secrecy. Harvey’s 1998 obituary simply states that, “he was a Canadian observer at the A-bomb tests in Australia.” But, at the time the British were beginning to consider the limitations of the small island testing site, according to declassified interviews with Dr. Alexander Longair, a former British senior scientist and director of atomic science with Canada’s Defence Research Board until 1967.

“During the long cold evenings in the huts on the Nullarbor Plain…the British fell to discussing how their high-explosive program to simulate nuclear explosions was constrained by working on a small and populous island, their limit being a few tons,” Longair said in a now-declassified interview from 1979.

“They suggested that Canada, with its large, relatively uninhabited open spaces could tolerate much larger explosions and hinted that there was a contribution we could make, especially since we now had the smoke rocket capability.”

Another Canadian at the tests, Jim Flynn, worked in London, and took up the issue along with Longair, and a program for large blasts at Suffield was secured.

“Our sights were set for an explosion of 100 tons of TNT, the great question being whether such a large amount of TNT would detonate completely and uniformly.”

That question would be asked and answered alongside hundreds of other tests and research projects conducted over the next decade by the three nations at Defence Research Station Suffield.

(Stephen Murray is a retired defence scientist who worked at Defence Research Suffield. This is an abridged version of a forthcoming book Murray plans to release on his career and specially on the Canadian Blast program. He is based in Medicine Hat.)

20

-19